Real-Time Simulation

DUECA, Delft University Environment for Communication and Activation

Overview

DUECA (Delft University Environment for Communication and Activation) is a middleware layer for the implementation and deployment of real-time simulations (or other computational processes) on distributed computing hardware. An application programmer can create “modules” in DUECA as self contained elements of a real-time computing process. The modules communicate within the simulation over “channels”, which can transport user-defined data types. DUECA then provides the following:

- (E) in a configuration script, modules are assigned to the appropriate “nodes” (computers), creating a simulation Environment that may be distributed over the available hardware,

- (C) the DUECA middleware layer provides the Communication between and synchronisation of the different nodes, transporting configuration data and the application data as appropriate,

- (A) DUECA Activates the modules’ activities as specified, either triggering on elapsed clock time or on the arrival of needed channel data, effectively creating the schedule in an automatic fashion.

This set-up enables an application programmer to develop simulation modules with little consideration of or knowledge on real-time programming aspects; decisions on thread use, distribution and scheduling priorities can be taken at a later stage, when deploying the simulation. The flexibility of the scripting language that is used to start and configure a DUECA simulation also enables testing at the desktop, typically with joystick input and several output windows for visualisation, limiting development time on the deployment hardware. All data communication is time-tagged, enabling debugging of the real-time properties of a simulation.

DUECA with its extensions (DUSIME, which is an interface for simulation control and dueca-extra, which is a library containing several auxiliary classes) was developed at Delft University of Technology, principally by its main author, René van Paassen, with smaller contributions by Joost Ellerbroek and Olaf Stroosma. It has an “ecology” of modules that have been developed by students and employees of the Control and Simulation division, with the more generic modules (motion filters, joystick and control loading hardware IO, generic 3D visualisation, UDP communication to external hardware) all developed by employees.

In over 15 years of testing by MSc. and PhD students in courses and for thesis work, and development and use by expert users, DUECA has matured to a stable code base. It is commonly installed on a variety of different Linux distributions, notably openSUSE, Fedora, Debian, Ubuntu, SUSE Linux Enterprise Desktop, and it is built for different versions of these distributions on the TU Delft’s OBS build server. Supporting packages are built on the OpenSUSE build server (https://build.opensuse.org). Examples of these supporting packages are a kernel with the REEMPT RT real-time patch, and the associated EtherCAT driver for IO with EtherCAT hardware, these are available at https://build.opensuse.org/project/show/home:repabuild:preempt and https://build.opensuse.org/project/show/home:repabuild:withupdates respectively. These are open source and available to anyone. In combination with DUECA this creates a high-performance platform for implementing distributed simulations.

Applications within the Control and Simulation division include simulation on desktop computers, the SIMONA Research Simulator http://simona.tudelft.nl/ and a smaller fixed-base simulator in the Human-Machine Systems Laboratory. DUECA is also used for data acquisition applications in the inertial sensor calibration laboratory, and for data acquisition and automatic control experiments in the TUDelft’s laboratory aircraft “PH-LAB” http://cs.lr.tudelft.nl/facilities/ph-lab/, where it handles the full set of ARINC channels from the aircraft databuses, as well as a number of analog, discrete and synchro/resolver inputs, storing all data in a fully time-tagged log and providing real-time data for visualisation and control experiments.

DUECA’s facilities for modular design promote re-use of code. Most of the simulations produced with DUECA combine a mix of existing modules and modules written specific for the simulation. A large body of existing modules, for example for communication with hardware such as control input devices, motion system, motion filters, out-of-the-window view generation is available to developers to quickly create a base for a simulation. The simulation may then be further extended by user-created modules. These can be written directly in code (e.g. C++), but it is also possible to create modules that encapsulate Matlab/SIMULINK models converted to c code with Simulink coder (Matlab, Simulink and Simulink Coder (previously Real-Time Work-shop) are software packages by The MathWorks, Inc.). A helper program is available to create a code framework for different classes of DUECA modules.

DUECA modules communicate through channels. Channels can transport DUECA Channel Objects (DCO), these are user-defined objects, that may have a complex structure. Using a simple specification language, an application programmer may specify which data members are part of a DCO. These data members may be native C/C++ data types (float, double, integer, etc.), but also more complex types, such as vectors, lists, maps or strings from the standard template library. DCO objects may also be nested, and users can extend the capabilities of DCO objects through custom code. DUECA channels and their DCO objects implement a single-inheritance model, in which a DCO object may be inherited from another DCO object, extending its parent. A reading client can then access the data in the channel through the child class or any of its parent classes.

As an example of the things that are possible with DUECA scheduling, timing and DCO objects combined, consider the WorldView visualisation module. This is an often re-used module for the presentation of 3D outside scenes. The module draws with the pace of the graphics card, typically 60 or 120 Hz. It uses the data from the simulation, which may run at a different rate of for example 100 Hz. When the scene is to be re-drawn, the positions of the vehicle and surrounding vehicles is read from the DUECA channels. The DCO object for the 3D view was extended with code for extrapolation, and this code is used to correct the position to match the video timing, resulting in fluent and smooth images.

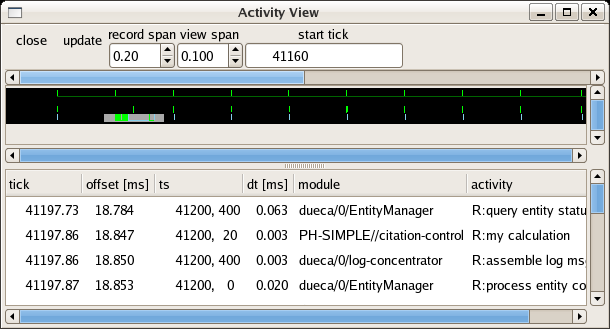

For controlling the different modules running over distributed hardware, DUECA implements logic for a distributed state machine. Using a default interface, end users can start and stop the processes implemented in DUECA. For simulation applications, the DUSIME extension adds additional state logic.

The current version of DUECA, 2.x, is available for a number of Linux distribution and also for Mac OSX.

Functionality

DUECA offers the following functionalities:

- Distributed real-time computation. The modules of a simulation or data processing program may be distributed over different computers. After starting the DUECA executables on these computers, a script with the module configuration will be communicated, modules will be created and the DUECA processes on these computers will synchronize execution; DUECA processes of up to 15 computers have been tested, theoretically the current DUECA version can handle 254 computers. The different DUECA processes may use different update rates, as long as these are compatible, i.e., have a common denominator.

- Flexible configuration. A DUECA simulation is defined in a configuration script; DUECA modules may be supplied with further variables from the configuration script, and since the communication uses a publish-subscribe mechanism, a script can offer a choice between alternative modules with compatible channel communication.

- Re-use, version control, migration and customization. The dueca-project script and the version control back-end offer tools for deployment on different platforms. Using metadata files, one can specify which modules need to be included in the DUECA executable for a specific computer, so that modules that require specific hardware devices or software libraries are only built when needed. The configuration for a platform – for example a set of computers connected to the hardware of a simulator – is also maintained in version control. This integrates development and initial testing on desktops or portable workstations, with deployment, configuration and final tweaking on target hardware.

- Modular development. The development process is targeted for – and extensively tested by – developers that have limited exposure to real-time programming. A module typically defines a single “Activity”, which is implemented by means of repeated calling of a method in the module’s class. The application programmer defines the module’s data members, and the channels that the module reads and writes. The method that implements the activity typically reads data from the read channels, implements the module’s calculation such as updating a model, or drawing a display, and sends any resultant data over one or more written channels. Channel reading and writing is thread-safe, and with a single activity, running at a single priority as defined in the start script, developers don’t need to consider real-time issues such thread-safety, race conditions, possibility for deadlock, etc.

- Time-tagging, determinism, robustness. All data in the DUECA channels is tagged with the “model” time. Time in DUECA is defined through increments, with a configurable duration. Channel data may be either event-like, associated with a single time moment, or continuous, describing the signal in the channel for a certain duration (from one time point to a later time point). Channels can buffer the data for a configured time span, offering reading modules access to data that matches their model time. Also when a calculation overruns its nominal time slot, e.g., when loading data on initialisation, and modules are delayed, calculation can still take place with data matching the proper time, making the end result deterministic. Time tagging and the synchronisation also mean that the age of data can be determined at any point, making any delays in a simulation explicitly visible and traceable.

- Schedule follows data. Based on the time tagging of data in the channels, DUECA can provide modules with “triggering” on data availability. Using temporal logic, the joint availability of data from different channels can be specified as a condition for running a module’s activity. The temporal logic ensures that the activity is run for the correct time intervals, also when data on one of the channels is delayed. DUECA can thus generate its schedule on the fly.

- Distributed state machine. Control of the DUECA modules is through a distributed state machine. An additional state machine for DUSIME adds states for simulation control, such as run and freeze.

- Hardware modules. DUSIME modules that interact with complex hardware, such as motion systems or control loading hardware, have additional safety activities and calibration states, to ensure careful handling of the hardware, proper transitions and a safety strategy for unforeseen conditions. The safety strategy is also invoked if for any reason the connection to the other DUECA processes is lost, so hardware can be restored to a safe state after a network failure for example.

- Code generation. Support scripts simplify creating the code for modules by generating code for different module variants. Comments indicate where adaptation by the application programmer are needed. For the module variants that encapsulate C code generated by Simulink Coder, also a test program is created that calculates the model’s response to an input specified in a file. This facilitates verification of the generated model against the original model in Simulink.

- Documentation. Using doxygen http://www.doxygen.org/ module documentation can be generated. The instructions for creating a module from the start script can also programmatically be generated, and are included in the generated documentation.

- Separating developer roles. The modular set-up, template code, configuration through the script and visualization tools enable late configuration and adjustment of the real-time process. Typically, at deployment on a hardware platform the final checks on real-time performance are done and tweaks – by selecting proper priorities are still possible. This means limited time from developers intimate with real-time configuration of DUECA is needed.

- Efficient communication. DUECA uses a binary communication protocol, and data is only transmitted over the network if that is needed. If data in a specific channel remains largely static, with only part of the data changing, one can specify that only the changes in data are transmitted. A “Bulk” transmission mode is also possible for channels with large data objects that can be transmitted at low priority.

- Advanced memory management. Memory management facilities are in place to minimise dynamic memory allocation, and if the application avoids constructs that use memory allocation during real-time running (notably stl containers being filled and emptied!), real-time determinism can be achieved.

Unique features

DUECA has the ability to implement a deterministic calculation process on distributed hardware, whereby the schedule is automatically generated. This feature is not due to a single component of the software, but only possible by the tight integration of several unique functions, notably the lock-free, thread-safe communication over the channels, with the time tagging of the data and the triggering and scheduling system. Each channel is also an active, triggering object, and by selecting the channel as a trigger for an activity, any write in the channel produces an invocation of the triggering temporal logic, which is then processed by one of DUECA’s schedulers. To reduce the code base and thereby increase coverage and checking of the code, different parts of the DUECA core code use the same facilities offered to application programmers for their internal organisation.

DUECA’s time tagging and scheduling result in robust real-time processes. One of our simulations uses an extensive visualisation for the out-of-the-window projection, that can take several seconds to load all required visual models. This happens at a time when the simulation is in a freeze mode, so for the simulation it does not really matter. No specific precautions for that have been added to the program, the module does overrun its time slot, but later invocations of the module’s activity can simply make up for lost time.

Many years of use by relatively inexperienced programmers – our students – have resulted in robust code. In the first years of DUECA, several small changes have been made to the application programmer interface with the objective to eliminate common programming mistakes, or at least make these as clearly visible as possible. As an example, generated code is supplied with a hashed “magic number” that is based on the types and names of the data members in a DCO object. At start-up the magic numbers from the different parts of DUECA are compared, and a mismatch is reported when found, eliminating a common problem where students had made small changes on one computer, but had not propagated the changes to other computers in a distributed simulation.

Performance monitoring

Real-time programs are typically difficult to debug, since a human debugger is not fast enough to check the real-time aspects of the running process. Typical solutions are snapshot tools to capture the state of a simulation at a specific time point or span, and simple logging/printing statements, to verify that certain points of the simulation are executed, or to signal problems in real-time running. DUECA offers a number of monitoring and verification tools:

- A timing overview shows the cycle times and relative times of the different DUECA nodes, and keeps an inventory of maximum and minimum response times of waking the highest-priority thread. In addition DUECA modules may be selected to provide timing information, specifying warning and critical levels of timing, and number of cycles to check. This timing information is presented in real time and logged.

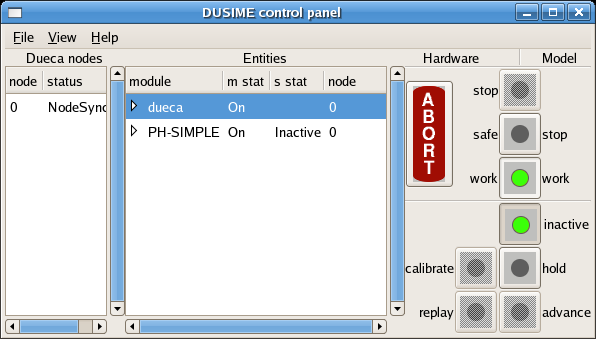

- The “activity” view can be used to take snapshots of the real-time schedule. Each node in the DUECA process is represented by a graph showing the start, end and duration of all activities for the span of the snapshot. Each scheduling priority has a separate line in the graph. Details on the specific activities can be viewed by selecting a part of the timeline, showing timing at the microsecond level, module and activity name for all activities in the selected piece of timeline.

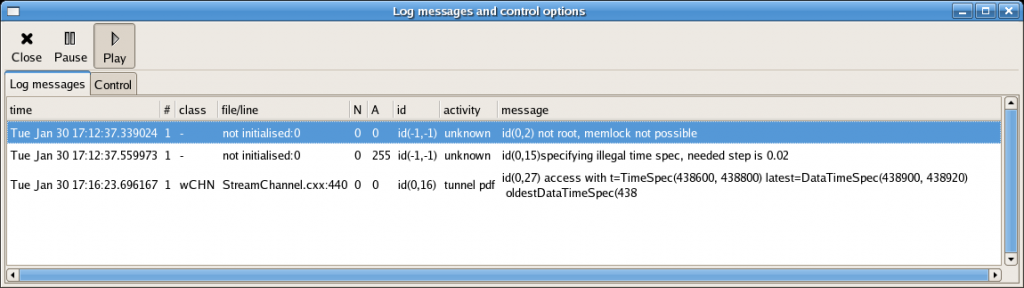

- The logging facility in DUECA ensures atomic logging messages, produced in finite time, and tagged with the file location, DUECA process number, priority level, activity and module id’s and a hit count indicating how many times the message was produced. The hit count is also used to throttle messages that are too frequent. Logging messages are both sent to standard error output locally, and transmitted to the coordinating DUECA node for presentation on a log view window and inclusion in a global error log.

- The run status of all DUECA modules is regularly checked and presented in the overview window.

- The run status (connected, synchronized) of DUECA nodes is regularly checked and presented in the overview window.

Conclusion

DUECA is a middleware layer targeted at creating integrated distributed simulations, typically on platforms with several to a dozen nodes/computers. It can interface with models generated from Simulink. It features modular development and configuration, a unique communication and scheduling mechanism that makes it easy to create and modify real-time simulations, and several tools for verifying the performance of the real-time process.